Today I am sharing an excellent interview that I engaged in with Dr. Peter Buckland of the Penn State University Sustainability Institute. I am on the mend from a summer episode of Lyme disease, with positive progress, and so I am posting Peter’s post from July 9, 2016. I hope you will enjoy this interview on solar ecologyas much as I did speaking with Peter. It was so fun! More posts to come soon–they were just backlogged due to illness. Forward!

You can find the original article at the website of the SI, and I also recommend looking into more of Peter’s personal thoughts at his blog, Peter is in the Forest, and following him on Twitter: @PDBuckland.

Peter Buckland: Your championing the adoption of a big concept, solar ecology. Why? Where did that come from?

Jeffrey Brownson:

Solar ecologyis meant to be a systems framework to engage in both discovery and design of the space of the sun, the light from the sun interacting with the earth, with the environment, with the solar technologies that we create and use, the solar technologies that we adapt for food, and the solar technologies that we live in (like photovoltaics, agriculture, and our homes, respectively). It is an exploration of patterns of the flow of light from the sun within the dynamic context of the place where we live and act out our lives. It includes the seasons, the ways stakeholders in an environment interact with each other and make decisions, and the ways we choose the technologies that we use in our lives. How do we use the sun? How do we perceive the sun? How do we understand the patterns of the sun interacting with the earth and our choices to design, adapt, and improve our livelihoods using that flow of light? It’s analogous to the way we usegeologyas a systems framework for exploring and discovering design of the earth systems around us.

PB: If I say “solar” to a typical person today, I bet they’re going to think of photovoltaic solar panels. But you’re talking about something that’s so much bigger than that.

JB: I think that thinking of

photovoltaics–or the conversion of light into electricity using those blue or black panels–is a really great starting point for thinking about solar energy. It’s very tangible. It’s right in front of us. It’s a hot topic. It begins a discussion to generate a conversation. If light can be used to generate electricity, then what else can light be used for? What else is light being used for? That kind of beginning dialogue to talk about photovoltaics for generating electricity and expanding it see that solar is part of our homes, our building systems, how solar is part of the light that you use to perceive the world around you, that it’s the functional element to creating the food around you, to creating wood products, and everything that we use to create modern society–it’s all at the core.

PB: Is there almost a solar consciousness you are trying to build?

JB: I’m trying to remind people that there always was a solar consciousness. But through the advent of readily available fuels our culture has forgotten its solar awareness, things as close back as our grandparents’ generation. There are ways of living that are tied closer to solar than we think. We’ve just a loss of core knowledge of how to use solar energy.

PB: How far back does that go?

JB: That’s a fascinating thing. The more you look at solar as the flow of energy that gets converted into many goods and services, you can track it back to building systems, to trees and agriculture. Finally, what you find goes back to the Neolithic revolution, over 10,000 years ago–to the beginning of the Holocene geological epoch. That’s when you see human society aggregating, becoming localized and fixed in one place.

They were cultivating agriculture–a solar energy conversion process, a design strategy for food and for the products for building the environments around them. And so there are fixed places and building structures to stay in one place, and they have to develop design principles for the buildings. How do those structures provide functionality? How do they provide shade on hot days? How do they take advantage of the sun to provide warmth on cold days and avoid fuels? You can look into ancient Mesopotamia to look at the beginnings of agriculture and civilization and see this.

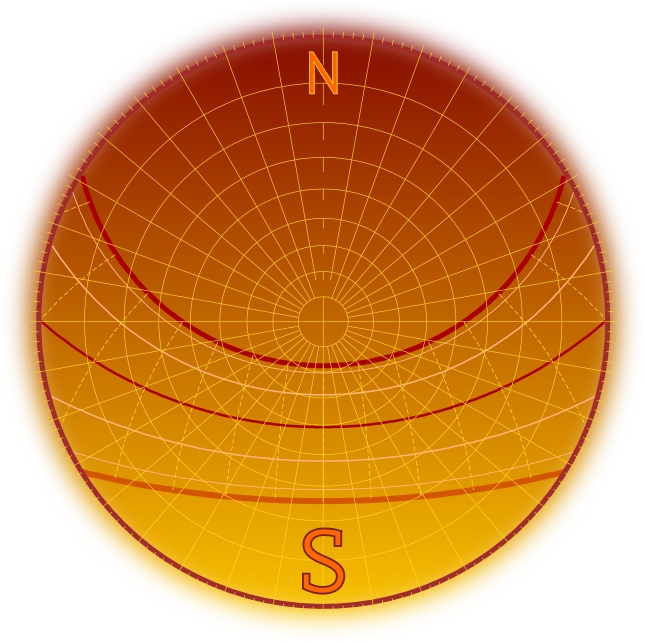

Gnomon at the Penn State Arboretum

But it gets more interesting about 6,000 years ago. John Perlin is a solar historian who’s pointed out that in China we see the emergence of what we call “

solar vernacular,” a localized design principle that works the way the culture works. We have the emergence of the first “gnomon,” sticks that stand out of the ground to tell time–we have a large one at the Penn State Arboretum. The very first curved mirrors were being used to start fires using sunlight at that time too. There were conventional requirements that you had to orient your buildings toward the equator. Living in the northern hemisphere you had to take advantage of the sun for warmth during wintertime.This is also coincident with deforestation that comes along with urbanization. Where you have deforestation you have a high cost of fuels (like wood), as those fuels are inaccessible. So what am I left with for useful energy in that case? I will go back to solar. We call that an “energy constraint response.” When fuels are available, easily accessible and cheap the sun is forgotten.

PB: Oil. Coal. Natural gas.

JB: Right. When fuels become constrained because they are physically inaccessible, if the demand outstrips supply, if it requires high risk (like a war) to access, or if a society puts restraints on the use of fuels, then those constraints transform society to go back to solar. Solar is ubiquitous, fast, and viable for solving problems.

PB: If you think about the oil shock of the 1970s, solar became a saving strategy for a time. And then it died away…

JB: …when fuels became more accessible.

PB: And in American and European history there are previous examples.

JB: Absolutely. There are waves of this across centuries. When there are fuel constraints you see new solar designs in buildings and agriculture. An example is that during the Little Ice Age in northern Europe people were building solar fruit walls or espaliers. They would pin fruit trees to a wall so you can grow fruit in a colder climate because the sun warms the back wall that creates a microclimate. So that becomes an aspect of the culture. It’s not like a technology that you go to school to learn how to do but something that becomes the vernacular, the common thing that everybody knows about and does.

PB: A few years ago peak oil folks were calling attention to peak oil. But they’ve lost some gusto temporarily because of the shale gas and fracking boom. You would think that solar would be getting pushed aside by the ubiquity of natural gas and yet it’s not.

JB: Part of that is that is looking at these fuels as commodities. Natural gas right now isn’t a global commodity. You can’t ship natural gas very easily. It has to be put through compression processes and liquefied. The main way you ship natural gas is through pipelines. That’s a physical constraint to fuel access.

If you counter that with solar, solar photovoltaics in particular for electricity generation, then you can put them anywhere. The modules themselves, the panels, are made and sold as a global commodity just as barrels of oil are. Their price keeps dropping as more photovoltaic panels are deployed on the planet. There are niche areas on the planet right now that need electricity and there’s no natural gas pipeline and no grid to provide electricity from coal or nuclear plants.

PB: Like much of Africa, Asia, and South America.

JB: Exactly. So we have this Anthropocene revolution, where we are seeing decentralized and local energy strategies and new solar vernaculars emerging. These will solve the local and regional problems of adaptation to and mitigation of climate change. I don’t see solar turning back at this point.

If you look back to the 1970s and 1980s solar was not a global commodity. It was still manufactured product that was local to a region of the United States or Germany or other areas where it was manufactured. Since then, solar has expanded beyond a tipping point, and now we have manufacturers in Southeast Asia that are beating out everybody else. The panels themselves are now just raw commodities. Most people don’t care about who the manufacturer is other than quality assurance and quality control. They just go out as readily available as TVs and phones, base products that you just buy and expect to work.

PB: In a solar ecology conception of community development and building, the local solar vernacular should dictate how development proceeds.

JB: Right. One of the beautiful things about solar vernacular is that it brings us back to local skill and local knowledge. You can’t outsource that skill and knowledge. You need to know how the weather works here…in this place. You need to know about access to water, rain, and the permeability of the land. You need to know local policies or the ways that local municipalities interact with one another, how they make rules, and how those can help or hinder solar solutions. All these things become very localized very fast.

PB: What are the traditions in the area even.

JB: How does the area see itself? If the area sees itself as a farming area then solar must be part of a farming strategy. If the traditions are looking at something other than electricity then how do you use solar for thermal applications, for hot air, for hot water, or for industrial processing? They’ve done that in Austria and other places for brewing solar beer. There are really cool strategies emerging.

I think one of the cooler things I’ve seen emerging–and that you hinted at–is attention to the community. What happens when the community leads it? Let’s take solar photovoltaics. It appears to be a turnkey solution that can be dropped in from on high. It’s just electricity on demand. Here ya’ go. You’re problems are solved. We now know that won’t work, and it will create new problems. If you haven’t developed human capacity to work with solar solutions by the time you’ve deployed them then you will have problems. Developing the solar vernacular is more important than the technology.

PB: An example of that would be what happened last year in Woodland, North Carolina where a community rose up against an energy company building a third solar power plant there. A corporate entity came in, built two arrays already, and the community rejected them because of a disconnection between what they knew, who they believed they are, and what they were going to get from the project. It looked like there was no relationship there. It looked like an imposition being put on them.

JB: Yes. Absolutely. And I think there are two parts to that. When any energy generation becomes big, it becomes “Big Energy.” Big Energy has large impacts and impositions on the people and places it’s deployed. You can’t get away from that. Just because photovoltaics might be a low-carbon energy source doesn’t mean it will have a low impact on the communities and societies where it’s grown to enormous proportions.

PB: So you could have a devastating enterprise that’s zero carbon powered renewable energy?

JB: Absolutely.

PB: So just because it’s solar doesn’t mean it’s egalitarian.

JB: Oh no. It doesn’t even mean that it’s environmentally safe. If it’s done wrong it can be hugely impactful. The classic example of that is the Dust Bowl. People were sent out and told “Go out and farm.” They were to be solar designers. “Grow food.” And what happened? They tore up the soil not realizing the destabilization they were causing. Suddenly a thousand acres became millions of acres of disrupted environment. Similar things could happen in a solar environment. If you just lay out photovoltaics and change the land use pattern then who knows what happens?

PB: Right. What happens when you have rainfall on hundreds of acres of impervious solar panels getting channeled in new ways?

JB: This becomes a discussion where we have to talk about the ecosystem services of a particular environment as part of the solar solution. How do those tie together? What’s the systems framework for tying those together?

PB: That really brings Aldo Leopold’s “Land Ethic” and Wendell Berry’s “Solving for Pattern” to the front. So this sounds like you’re bringing together community processes, the deployment of technology, and how it fits in the land.

JB: Yes. We would use the term “

solar utility”, which is a preference for solar goods and services. That can be meadows, trees, agriculture, or photovoltaics. If you go to a community and develop a project and you show no good to them, no utility, no solar goods and services for that community, then you are working against good solar design. You’re just extracting the solar energy resource from that community and shipping it someplace else and negatively impacting them. That kind of thing can “poison the well,” so to speak, by generating antagonism against solar technologies.There is definitely a wrong way of going about deploying solar technology. The folks in Woodland saw that. They had no return of solar goods and services coming their way. They saw a disruption of their land, maybe forest or hunting land and nothing given back.

PB: Like employment.

JB: Like employment. So the folks deploying it were not using good solar design, which is for higher preference for solar goods and services to the stakeholders in a given locale.

PB: So I want to ask about climate change. Big solar is very attractive. When you get a whole lot of money thrown at a problem you can move fast. How fast can what we’ve been talking about happen? If you look at the Paris Agreement’s goals of a 1.5 degree Celsius limit, we don’t have much time. According to an analysis by Carbon Brief, the carbon emissions budget for that will be used up in five or six years if we want a pretty good chance of meeting the goal.

JB: I’m not just referring to photovoltaic technology. That technology can be deployed in very short periods of time. Months for huge arrays. Years for gigawatts worth of energy. It’s very easy to put in the ground. But where’s the human capacity coming from? Where’s the skill set coming from, so that as we do the solar development we aren’t just exploiting regions all over the planet in the name of providing low-carbon electricity? It may or may not be the right solution for each region.

We should develop local capacities for understanding, for understanding solar within that place and time, meteorology, and community engagement. That means education and developing solar understanding across all the disciplines. It can’t just be science, engineering, technology, and math (STEM). It has to be a cultural phenomenon. To me, that’s the only way we are going to get a very rapid change for solar, when we relink to solar awareness.

PB: Readers and contributors of and to this blog come from across the disciplines including climate science, geoscience, psychology, poetry, photography, and education. We have the breadth of solar ecology. How do we bring it into art, literature, philosophy, or social studies education?

JB: The wonderful thing about solar is that it’s been around for a very long time. The story of solar is the story of people living in place. Its message is embedded in some of our norms. When we have a porch or a patio, it was originally designed to face the south to be a shading mechanism during the summer time and to let sunlight in during the winter to heat your house. It comes from the portico in Italy and Greece a long time ago.

There are stories. In South Africa we have the story of the Little Man and the Big Man carrying the sun across the sky. When the sun is high in the sky in the summer the Big Man is carrying it. In the winter when the sun is lower, the Little Man is carrying it. We have ways of visualizing and telling the stories of our changing environments and seasons.

You wouldn’t have that story in much of India, where the sun is a little to the north or a little to the south but the days are generally about the same length. In designing a home in India you want a southern facing door, but that has nothing to do with the Sun. That has to do with wind coming in and cooling your house to keep it comfortable during monsoon season. All of this can come in story and song.

When you embrace the message of solar in a way that becomes part of our livelihoods there opportunities for many, many disciplines.

Original interview attribution: P. D. Buckland. Penn State Sustainability Institute. Posted July 9, 2016