Highway to the Shadowy Tip of Reality

Imagine a cool kitchen in the fall, or a cold garage in the winter, imagine a stifling hot music hall before a concert, or the frigid cool of a grocery store near the frozen goods section. Is your “hot” like mine? Do you overheat in the New Orleans afternoon in June, or go for a stroll? Is your “cold” comparable to the North Dakota winters that I grew up in, where your skin can freeze in under a minute?

You see, thermal comfort is personal, developed, conditional…that environmental-body exchange to emerge as thermal comfort is also regional, cultural, and even transitory with the seasons. And when we think of thermal comfort we often associate it with the valued metric of temperature. But body comfort is not the same as temperature. In fact, there are many many factors that affect our bodily engagement with our surroundings and the emergent sensation that we ascribe to comfort (relative humidity, CO2 levels, particulates, air flow, etc.) When it comes to adapting to meet comfort inside of a room or hall though, what we would call conditioned space, temperature becomes our go-to proxy to adapt and change the space (conditioning the space with air…voila: air conditioning).

What helps us to regulate our interior spaces in the modern day? The theromostat: the transformative feedback technology to measure the system’s air temperature relative to a desired “set point,” then switching heating or cooling on/off to meet that temperature condition. They control our central heating and ventilation fans, our window unit air conditioners, they control our ovens and our refrigerators. And at the core of a thermostat is a thermometer of some form (often a thermistor device).

Now imagine a conference room where we have congregated diplomats in suits from Nigeria, Germany, the USA. One person is freezing, one person feels the room is uncomfortably cool, and the American is looking for a wall control to make the room colder, because it feels “stuffy.” Only she cannot, because today the

thermometer, the device to measure the temperature of the space in a normal thermostat is just not there.

What’s wrong? This is a world with no thermometers, no system of measurement to provide information, feedback, or learning to people or to smart computer control systems. In our world, there are numerous measures of temperature, relative humidity, and even CO2 concentration that contribute to comfort in a room–but here, in this world, imagine that you do not have access to any of them to aid in communication, learning, and control.

This is my world, the world of solar energy–where there is no public value for measuring light, and there are effectively no solar “thermometers” available for the public.

“This highway leads to the shadowy tip of reality: you’re on a through route to the land of the different, the bizarre, the unexplainable…Go as far as you like on this road. Its limits are only those of mind itself. Ladies and Gentlemen, you’re entering the wondrous dimension of imagination. . . Next stop The Twilight Zone.” –Rod Serling

Solar Culture Sleeps: Where is it?

The culture of solar energy and light exists, seemingly just below the surface of society, in a dreamtime that has passed with our great grandparents. We have become asleep to the culture of solar energy, to the culture of light, particularly at home. That solar culture has access to a dormant solar vernacular tied to place and time (called the locale); to seasonality, daily fluxes, and even momentary strategies for standing in the shade on the corner of a hot summer day; tied to solar design and practice in travel, farming, and home care; and the story of solar caught in verse, proverb, image, and song.

“Only mad dogs and Englishmen go out in the noonday sun.” –Indian Proverb applied to the Indian

locale

Practical solar and light knowledge in the Global North has been temporarily washed away by the remnants of the industrial revolution, modern design, and an excess of high density energy geofuels. But look around in the nooks and crannies of other cultures, look to the stories of our elders, and you will be pleasantly surprised.

Light at Home

Think of optics (meaning light-matter interactions, not political framing) within a functioning microwave oven. We cook every day with light, and yet never question or acknowledge the power of photons causing water and fat molecules to wiggle and twist until “hot.” This is light absorbed by matter , to produce a desired result of rising temperature, melting, or evaporating–something we call optocalorics. Unfortunately, nobody really measures the light to acknowledge its existence.

Hey, that’s a light-based oven mounted above a gas-combustion oven!

And that’s a big problem. You can put a thermometer into a pot of stew and measure the temperature of your food, but nobody really measures light with a common household tool or device. Light is a wispy thing that can only be described qualitatively, like comfort in a room, and then using the relative skill with our light-adaptive eyes. Light, in our present world without thermometers, is bound by the limits of the human eye. Light is defined by the physicality of the human body–the non-standardized “cubit” of our modern day dreaming light culture.

Embedded Ethics of Measurement Choice

Scholars and philosophers of ethics would call this a result of embedded values that strongly affect the choices of what we measure–how do we choose the explore our environment, or how is research itself constructed. We call this reflexive inquiry embedded ethics (or intrinsic ethics). Our recent contemporary, urban, insular societies have steadily disconnected from our supporting environments, our locales, have washed away the representation that light is important, is valued, and as a result needs to be measured. With no intrinsic value for the broad spectrum of light, we have no thermometers for light, not in a general sense.

Some of you may be photographers, architects, or interior designers–crying out “WAIT”: we do measure light, every day! And my response would be–“thank you!” for pointing out the first example of embedded ethics as a choice of measurement. For the specialized devices that are used in these spaces of society are called photometers, which have the valued but bizarre task of measuring only the light that would be perceived effectively by the cone cells, the three color photoreceptors of the average human eye.

RadioLab Podcast:

“Rippin’ the Rainbow a New One” The “color for others” section can be found at ~8:30m. The color science discussion is “mixed in” well with choral musical representations!

In this phenomenal 20 minute podcast on light (“Rippin’ the Rainbow a New One”) from RadioLab, we learn from neuroscientist Dr. Mark Changizi, and visual ecologist Dr. Thomas Cronin, and color vision researcher Dr. Jay Neitz about just how different color vision is for other beings in our world. Your dog has two cones, we have three, a sparrow has an extra fourth ultraviolet-light cone, and butterflies can have many more photoreceptors than humans to see into the ultraviolet, the deep red and more. Wow! But wait, there’s more.

Then there is also the mantis shrimp, the swift-punching super-sonic invertebrate with 12-16 photoreceptors (remember, we have 3 cones, and that defines how we measure light–the visual version of the cubit again). To be clear, the mantis shrimp doesn’t use the cells in the same way that we use our three sets of cone cells, but it does access light in a very different way than we humans. For many of us, this will be the first time we even learned that other organisms measure light differently than ourselves (using their eyes, that is…). This should really begin to pull at your certainty in the singular value of the average human eye (not to mention the prevalence of color-blindness in a sub-set of men in society), right?

Behold: The mighty Mantis Shimp! Credit: Charlene McBride CC-BY-2.0

Eye and Candle Measurement: Standardized

Here is where the weird world of photometers comes in. When we measure light (for photography, architecture, or interior design), what most people mean by that word are the wavelengths of light perceived by the human eye that impart color to the brain (the cones and, to a lesser extent, the dim light receptors called your rods). In society, we have come to value visual light. We value it so much that we invested a whole base unit of measurement on it, and then a whole system of strange technologies that measure only the light that would be perceived effectively by the photoreceptors of the average human eye. Not the sparrow, not the butterfly, definitely not the mantis shrimp…only the human eye. In fact, the International System of measures (SI units, the metric system) has one ‘fundamental’ unit assigned to a valued phenomena in society, called “luminous intensity”: the candela (cd), based on the luminosity function, a non-fundamental function modeling the apparent sensitivity of the average human eye.

It get’s odder. Because with any light transfer, you need both a source to emit the light and a receiving sink to absorb the light. The light from the sun is great, but then there is that pesky spin of the planet that delivers the night upon us. As you know, light during the night is alright–from a bonfire, to a street lamp, to an itty-bitty LED book light. But back in the day, way waaaay back, the standard non-electric source of light was established through burning of a wick embedded in a fatty waxy tube. Yep, we’re talking candles now. Before 1879–the production of the electric incandescent lamp from Edison–lighting the night meant candles.

Credit: User: Bangin, Wikimedia Commons. CC BY 2.5

There is a detailed, comprehensive, 580+ page report available from the International Energy Agency, exploring the historical context and economics of artificial lighting; called “Light’s Labour’s Lost” (2006, Waide and Tanishima), a word-play on the title of one of Shakespeare’s comedies from the 1590s: “Love’s Labour’s Lost”. The authors comment that, in order to write during the night, Shakespeare would have needed light from tallow candles, which would have offered at a present day cost of around US$16 per thousand lumen-hours (meaning a measure of all the visible light emitted from a source, for a given hour). That would be about a single year’s supply of tallow candles–nearly 2 kg for one person. Tallow was a cheap fat to use as a candle base, and far more smoke-rich than the alternative of whale oil, during the brutal cetacean-powered light boom of the 1600-1700s–weird times. Today, those thousand lumen-hours would be accessible for a negligible amount of money: just over a hundredth of a penny–light is so cheap now (if you have electricity).

“When the incandescent lamp was first commercialized the main mode of transport was the horse, trains were powered by steam, balloons were the only means of flight and the telegraph was the state of the art for long-distance communication. Much has changed in the intervening 127 years [up to 2006], but much has also remained the same. In 1879 the incandescent lamp set a new standard in energy-efficient lighting technology, but today good-quality compact fluorescent lamps need only one-quarter of the power to provide the same amount of light.” –Light’s Labour’s Lost (2006) Paul Waide and Satoshi Tanishima

And so, by 1946, when the rest of the SI units were being established, an additional fundamental, valued unit of measure was established for light (right up there with the meter, the kilogram, and the second), and called the candela. Up until the 1970s, the candela really was a measure of source light emitted from a burning wick and wax of rendered sperm whale fat called the “Standard Candle” (see spermaceti–because rendered beef or mutton fat was far too smoky), somehow also related to the light emitted by platinum at its melting point; light which was then received and absorbed by the model of an artificial average human eye, one without an iris or eye lid, visually perceiving color and dim light.

I give you the modern day

cubitfor light: the value and measure of light emitted from a whale candle and absorbed by a lid-less eyeball, apparently attached to a brain in a vat.

Credit: User:Was a Bee, Wikimedia Commons Public Domain.

Only Terry Gilliam or Terry Pratchett could have done better, and at least they would have been joking with us. Times have since changed, but the title of the candela and it’s deep association with combustion and human vision still remains (and then there is the lumen, the lumen-hour, the lux). Sound confusing? Is there any reason that we should be surprised that lighting guides comparing LED lamps to compact fluorescents to incandescents are like reading ancient runes?

“The value of the new candle is such that the brightness of the full radiator at the temperature of solidification of platinum is 60 new candles per square centimetre” (CIPM, 1946)

Needless to say, visual lighting literature is rich, convoluted, and a bit confusing. But you see the results of that measurement basis in all of our new LED lights. The lumen tells us how to compare the lighting efficacy of that new technology against the old “60W incandescent” light bulb in your grandparents reading lamp. The very notion that electric power demand was used as a reliable proxy for lighting efficacy is yet another story of embedded ethics…

Moving on to a future with thermometers!

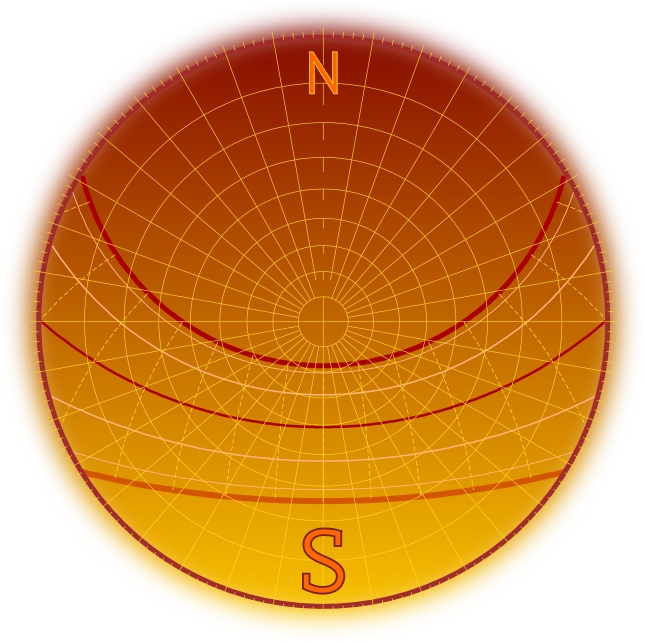

The practice of measuring shortwave light–the broader band of light that is not guided by the human eye (the UltraVioloet band, through the Visible band, and all the way through to the InfraRed band)–is done by radiometers. Radiometers which, truth be told, do exist in niche spaces of society tucked away for meteorology, defense, monitoring sunlight variability for big solar farms, and in my own little pocket of solar science research. Radiometers are just not everyday items like thermometers. But someday, they will be–motivated by our shifting culture to one of light for both energy and communications.

And now, even for the international systems of measurement, pressures are mounting to push for a new operational definition of the candela far away from the limitations of a candle and a human eye, one that is associated with quantum effects for individual photons: the quantum candela!

In today’s advances with data communication, we already use fiber optics to share information via light packets along a glass filament “pipeline” over hundreds of miles. We are beginning to use light to pass information in computers instead of electrons. We use laser light and LED light to project images and data on walls and big screens. We also communicate with light across space–the wireless communication network of radio, cellular phones, and WiFi are all part of the light spectrum, and yet each is seemingly hidden, in that dreamtime space, just under the surface of our collective awareness.

Q: Is that light? A: Probably, yes.

The light will out friends!

-JRSB

PS: Special thanks to Dr. Stephanie Vasko, for long discussions and correspondence on the concept of embedded ethics in science and society.

More Reading is Fun!

- CO2 and indoor comfort: higher concentrations, like in poorly ventilated lecture halls, tends to make your skin crawl and you feel sleepy.

- Anthropology paper reviewing the history of the cubit: Mark H. Stone, “The Cubit: A History and Measurement Commentary,” Journal of Anthropology, vol. 2014, Article ID 489757, 11 pages, 2014. doi:10.1155/2014/489757

- Recommended ethics paper discussing embedded ethics/intrinsic ethics in the context of climate research: Nancy Tuana, “Embedding philosophers in the practices of science: bringing humanities to the sciences,” Synthese, vol. 190(11), pp. 1955–1973, 2013. doi:0.1007/s11229-012-0171-2

- Hyperphysics science page describing Rods and Cones of the Human Eye. Credit: C. R. Nave.

- An absolutely fabulous RadioLab episode on Colors describing the rainbow for birds and the mantis shrimp.

- Book on Visual Ecology by Cronin et al.

- A deep, long, dive into the meaning of artificial light, and the argument for compact fluorescent lights (from 2006, right?) from the IEA: Light’s Labour’s Lost. written and researched by Paul Waide and Satoshi Tanishima.