“Time is an enormous, long river, and I’m standing in it, just as you’re standing in it. My elders are the tributaries, and everything they thought and every struggle they went through and everything they gave their lives to, and every song they created, and every poem that they laid down flows down to me – and if I take the time to ask, and if I take the time to see, and if I take the time to reach out, I can build that bridge between my world and theirs. I can reach down into that river and take out what I need to get through this world” –U. Utah Phillips

Today is a mash-up of two great contributors to society, each of whom have rested just on the periphery of our common knowledge. Today we look to participants that have helped me to see the shape of the story of solar, each of whom had such an impact on my work and my livelihood in this new space of Solar Ecology.

Utah Phillips (1935-2008)

You may have heard of the box-car troubadour, labor organizer, and storyteller Utah Phillips (1935-2008) from his collaborative period with Ani DiFranco (The Past Didn’t Go Anywhere–released October 15, 1996, by Righteous Babe Records. I was strongly affected by his voice and message of time, story, pacifism, anarchy, and the malleability of our roles in this particular part of the river we find ourselves standing in. I happened to be working at a disc and comics shop part-part time (because really, music and comics?), and that was the right place, right time. Hearing Utah speak on the sound system was like tuning in to hear your elders, and it was an addictive message–one that made you go out and look for more! And so I would find myself looking into other small spaces for messages that ‘build that bridge between my world and theirs’.

Attribution: Fiona Bearclaw, Wikimedia Commons: CC BY 2.0

So time to listen to the story of one of our European elders, formed in a time of privilege for the elite, and discoveries that really seemed to remain hidden from the current story of solar that we are telling in school today. So today’s bridge between worlds takes us to our second contributor, from the 1700s Swiss Confederation…

Horace-Bénédict de Saussure (1740-1799)

Chances are significantly lower that you would have heard of de Saussure. In fact, I can probably guarantee that unless you are a reader of my solar historian colleague and friend, John Perlin, or you speak French and are an avid fan of 1700s natural philosophy and mountaineering, you haven’t had the opportunity to learn about a very interesting contributor to our story of solar.

The work of de Saussure came about in the period of the aristocratic natural philosophers in Europe. Now, in our time of science and specializations, when you search for him online, you will see Saussure listed as a university professor, a physicist, a geologist, the founder of alpinism or mountaineering in Europe, an inventor, and an explorer of solar energy science, among many other things. While his family was originally French, arriving in Geneva after the Reformation, Saussure was born in 1740 to an aristocratic family with connections to learned families throughout Europe.

After following through with higher education, de Saussure took to the mountains in the region around him, and seemed to explore everything that had to do with the mountains: from the sky above, to the flora surrounding, to the rock underfoot. He called the mountains “Nature’s laboratory”. On top of that, he was big on documentation, and wrote prolifically about his experiences climbing the Alps.

Saussure on Mont Blanc, by Marquard Wocher (1790). WikiMedia Commons: Public Domain.

Perhaps one of the most interesting things about de Saussure–for me–is that he was multi-faceted, and people with passions from different fields today find him to be a significant contributor for totally different reasons. He wrote compelling documentaries of his climbing adventures, the plants and glaciers, the minerals and the sky. He documented his climbing of Mont Blanc later in life (along with about 18 porters–did I mention the family was from the aristocracy?), the highest peak in the Alps. When he went out, his team carried instrumentation like thermometers and barometers, and they documented the natural world by the measures that de Saussure came to value. And he made some of the first documented measures of solar energy conversion in Europe, which has contributed to our understanding of the greenhouse effect of the atmosphere. So he now has a story within the foundations of mountaineering, the growth of geology, and atmospheric physics, along with an important role in the development of what we now call flat plate solar energy conversion systems.

De Saussure invented new technologies to measure the meteorology around him: the clearness of the sky, the “blue-ness” of the sky (skies are darker blue at increased altitude), the static electricity in the air, and the moisture in the air. Now imagine, making measurements at changing elevations, with instrumentation–this was big, and this was hugely important later to the field of atmospheric science (in particular to the establishment of mountain measurement stations). Indeed, there is a striking connection between mountaineering and detailed measurements of the surrounding environments. Maybe we need an article on the connectivity between science, design, and mountaineering? Send me your links if you have them!

Heliothermometers: The beginning of an era

Back to de Saussure: you know how you can go to the peak of a mountain in the middle of the summertime–the air will be much cooler, and there can even be snow (along with retreating glaciers)? Then, when you get back down into the valley areas at the foot of a mountain, the surrounding air is warm and pleasant. Why is that? We have our own personal observations that people get sunburns much more readily up on the mountains (or snow skiing), so it probably isn’t a reduction in the “amount of sunlight”, right?

On the other hand, there is a ridiculous yet fun episode of the television show BrewDogs, wherein the producers seem to need to go to the top of Mount Evans in Colorado, USA (+8985 ft. above Denver), to use the Sun to heat water. The hijinx that ensues is a classic study of how far we have fallen in terms of solar energy understanding (really, shiny reflective metal is supposed to absorb light? and then we heat up rocks to boil the water??). Now, solar brewing is real, both from PV power and from SHIP (Solar Heat for Industrial Processing), and the connectivity between solar energy and local beer is being explored all over the world (sounds like another post is brewing…what fun!). But moving on: we are more or less 93 million miles from the Sun, and so being 1.7 miles closer to the Sun at the top of Mount Evans will increase the average irradiance a bit, but it probably doesn’t make a huge difference, right? So what gives here, in terms of the science of sunlight and the top of a mountain?

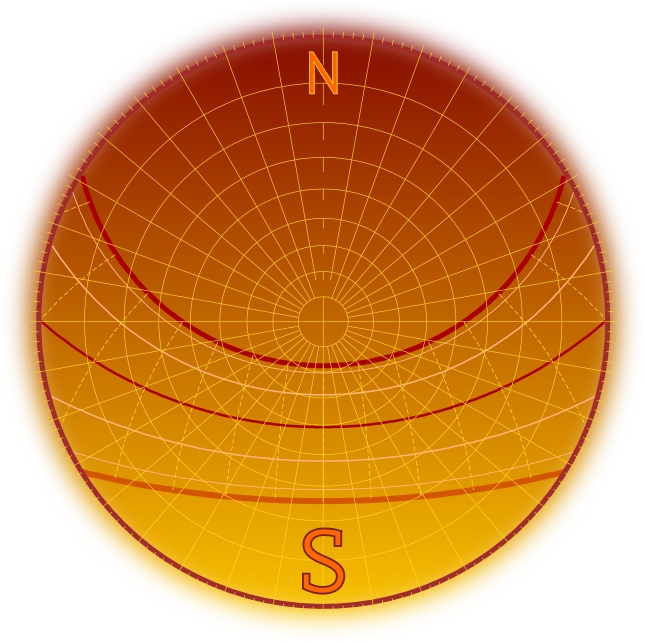

In the 18th century, de Saussure was deeply interested in this phenomena of cool air at the peaks of mountains, and so he built a rather clever device to indirectly test the irradiance at he top of a peak vs. at the bottom of a valley. He called the device a heliothermometer (the first solar hot-box), measuring the intensity of the light from the Sun. While other contemporary investigators like Priestley and LaVoisier were still investigating the uses of concentrated light via burning lenses, de Saussure wanted to know about the limits of the unconcentrated light within a glass box, along the lines of the greenhouses or windowed rooms, or carriages. Essentially, he inserted a glass thermometer into an insulated box with a black carbon soot interior (to absorb light), along with a top cover of one or more glass sheets that would permit sunlight to enter. This is the essence of a flat plate collector found in solar hot water panels today.

Attribution: Solar Cooking.org Accessed: July 31, 2016.

Here is an excerpt on de Saussure from my Open Educational Resource solar course at Penn State, EME 810:

He began to explore the role of a glass cover on a confined space like a box or a room. In the 1760s, de Saussure observed the following: “It is a known fact, and a fact that has probably been known for a long time, that a room, a carriage, or any other place is hotter when the rays of the sun pass through glass.” To find out how effective a glass cover works to trap solar gains, de Saussure constructed a large flat pine box that was insulated inside, with a glass cover on top. Inside the box he placed smaller boxes. When the flat cavity-cover absorber was exposed to the sun (no concentration), the internal box heated to 109 °C (228 °F), which is 9 degrees higher than the boiling point of water.

Peaks and Valleys, Sunlight and Earth-light

De Saussure then proceeded to the Cramont on the Italian side of the Alps, on Mont Blanc, and found heliothermometer temperatures similar between the summit of Cramont (87.5°C) and those on the plains near Courmayeur, Italy (86.2°C), nearly 5000 feet (1515 m) below the summit. That is only about 1 degree of temperature increase over 5000 ft of elevation change! In contrast, the air temperature readings outside of the box were 6°C at the summit (81.5°C colder than inside the box), and 24°C in the plains–18 degrees decrease over 5000 ft of elevation change. So yes, a small increase in irradiance at the summit, but overall a huge decrease in the ambient air temperatures as one scales a mountain. So what is happening in the natural world that would lead to lower temperatures at elevation, when measurements show a slight increase in irradiance?

“The principal reason for the prevailing cold on high and isolated summits, is that they are surrounded by and chilled by air which is constantly cold. This air is cold because it cannot be strongly heated, neither by the rays of the sun, due to its transparency, nor by the surface of the earth due to the distance separating them.” –De Saussure, 1779-96 (Voyages dan les Alpes, Précédés d’un Essai sur l’Histoire Naturelle des Environs de Geneve, Vol. 2, Ch. 35. p. 932.) [Source: R. G. Barry, AMS (1978)]

Today we see this cooling is due to the role of the atmosphere and air chemistry as a transparent “cover” for the planet. Sunlight (shortwave band light) passes right through our clear-sky atmosphere (clouds aside), while Earth-light (and sky-light; each called longwave band light) is absorbed and then re-emitted by chemicals in the air (i.e. everything glows). In later centuries after de Saussure, researchers like Irish physicist John Tyndall (also a mountaineer) would develop the language of “radiant heat” and the interaction of water vapor and carbon dioxide to the non-visible longwave band light, glowing from the Earth’s surface and the air itself as “thermal radiation”. The atmosphere is a mixture of gases that includes the water vapor and carbon dioxide that Tyndall identified as crucial to absorbing and re-emitting longwave band light. At a simplistic level, the thicker the cover, the warmer the surrounding air. The unmixed air at higher elevations is essentially a “thinner cover” than that found at sea level.

NOAA’s Mauna Loa Observatory following a snowstorm. Attribution: Mary Miller, Exploratorium.

And so we have a linkage, from the measurements of de Saussure in the 18th century, to the theory of Fourier, and the laboratory experiments of Tyndall, to arrive at the essential concepts of the greenhouse effect developed even later by Svante Arrhenius in the 19th century, in our earliest climate models. Since 1956, measurements of global carbon dioxide concentrations have been performed on the top of another mountain, the NOAA Mauna Loa Observatory in Hawaii, USA. So now we know, the sky is a cover, and the Earth is one big hot box!

Final Digression on Optocalorics

Again, today we could call the heliothermometer a kind of flat plate collector, much like a modern solar hot water panel. The resulting change in temperature from light being absorbed (what we now call optocalorics) was strongly influenced by the role of the glass cover(s) reflecting or re-radiating the light back into the hot-box. A lot of people in popular science writing call this invention the first solar oven, which is only partially correct. De Saussure did take the opportunity to cook fruit in his box, making them “juicy”, but the major significance was in the results found at major elevation differences. This convolution of discovery and functional design actually shows us the amazing connections found in solar ecology, between the discovery of the world around us, and the exploration of design for functional uses found from conversion of sunlight into goods and services (cooking is a service, right?).

Even more research came about years later by explorer/naturalists, with successive work in heliothermometer development that led to boxes within boxes, within boxes; each with glass covers. In 1830, astronomer Sir John Herschel made a hot-box of his own while on expedition in Cape of Good Hope, South Africa: he confirmed de Saussure’s observations in the southern hemisphere, and then cooked eggs with his instrument.

In 1881, astrophysicist and inventor, president of the American Academy for the Advancement of the Sciences (AAAS), and third Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, Samuel Pierpont Langley, also constructed an informal heliothermometer with a copper pot and two glass covers, to test at the summit of Mt. Whitney in California, USA (over 14,000 feet above sea level). Water was boiled, fun was had, and Langley duly reported his work in the journal Nature in 1882, and then published extensive work to the US Government (Professional Papers of the Signal Service) in 1884…but didn’t cook anything. A swing and a miss! To his team’s great credit, they had much more advanced equipment, and were seeking the value of the solar constant (now found to be 1362 watts per square meter) along with key properties of the atmospheres ability to retain thermal energy and transmit light across different wavelengths.

In the end, light is light: an electromagnetic phenomenon (or, radiant heat) which interacts with solid matter in unique and rewarding ways. With de Saussure, we have an emergence of optocalorics for unconcentrated light, devices that source, detect and control light related to thermal behaviors.

Here, we present a working term broadly describing the conversion of light to thermal energy forms. As a frame of reference, we begin with the term calorimetry, the science of measuring the heat of physical changes (sensible heat), chemical reactions (latent heat), as well as heat capacity (specific heat). The caloric response in a material can be derived from optical methods, as we observe from the Sun heating the Earth, or a microwave heating a cup of soup. Next, the study of light and the interaction of light and matter is termed optics. We seek a common term to refer to the coupling of optics with caloric responses. Hence, we arrive at a logical conjugation of opto- and calor- to derive the science of optocaloric technologies. This term is application-based, as is optoelectronics, and should be explored for extended meaning. For example, one could use the term for solar cooling, not just for solar heating.

–JRS Brownson, Solar Energy Conversion Systems (2013). Academic Press. Ch 4 p. 72.

There is this whole rich space for expansion in optocalorics–can’t wait to see you all absorbing the fun and sharing the many new discoveries waiting for us all out there! And now, let’s bring it on back to our modern troubadour, Utah:

“I have a good friend in the East, who comes to my shows and says, you sing a lot about the past, you can’t live in the past, you know. I say to him, I can go outside and pick up a rock that’s older than the oldest song you know, and bring it back in here and drop it on your foot. Now the past didn’t go anywhere, did it? It’s right here, right now. I always thought that anybody who told me I couldn’t live in the past was trying to get me to forget something that if I remembered it it would get them serious trouble. No, that 50s, 60s, 70s, 90s stuff, that whole idea of decade packaging, things don’t happen that way. The Vietnam War heated up in 1965 and ended in 1975–what’s that got to do with decades? No, that packaging of time is a journalist convenience that they use to trivialize and to dismiss important events and important ideas. I defy that.” – U. Utah Phillips

The light will out friends. -JRSB

More information:

- For a fascinating look at SHIP for brewing in Austria, see the Göss brewery from Heinekin.

- For an amazing short read of HB de Saussure’s inventive work, refer to the document prepared by the Musée d’histoire des sciences, Geneva (2011): “The skies of Mont Blanc: Following the traces of Horace-Bénédict de Saussure (1740-1799) Pioneer of Alpine meteorology”

- Concept and text: Anne Fauche and Stéphane Fischer (Musée d’histoire des sciences, Geneva)

- Translation: Liz Hopkins

- Graphic design: Corinne Charvet, Natural History Museum, Geneva

- Printing and production: Bernard Cerroti, Muséum d’histoire naturelle

- Musée d’histoire des sciences, Villa Bartholoni, Parc de la Perle du lac, rue de Lausanne 128, 1202 Genève

- Web : www.ville-ge.ch

- De Saussure’s work was recognized in the 1978 AMS article by R. G. Barry “H.-B. de Saussure: The first mountain meteorologist”

- For a longer read of de Saussure’s role in the history of solar energy (and beyond), try John Perlin’s book: Let It Shine: The 6000-Year Story of Solar Energy

- Notable namings attributed to de Saussure:

- An entire Genus of alpine plants were named after him: Saussurea are thistle-like plants.

- A mineral aggregate was named after H-B: Saussurite is an aggregation of hydrothermally altered plagioclase feldspar, discovered on the slopes of Mont Blanc by de Saussure.

- The report by S. P. Langley is available to the public via Google Books: “Researches on solar heat and its absorption by the earth’s atmosphere: A report of the Mount Whitney expedition” (1884)

- The Nature volume with S. P. Langley’s report on solar research is also available to the public via Google Books: “The Mount Whitney Expedition” Aug 3, 1882, pp. 314-317