Let’s just get this out of the way: I like words, a lot. I like the history of word development, the way that words change over time, the way words are mutable (even mercurial) and not fixed. I embrace the way that words can shape our imaginations, and offer potential for new spaces in our world. I also thoroughly enjoy the act of word crafting, bending words into new spaces. I firmly believe that words are the vehicles to enact change in society, and the viral adoption of some words have changed the way that we see the world that we are a part of. Just think of the words light, energy, and solar, and you have inherent perceived meanings for each that are shifting quickly in today’s society of climate changing, wireless communications, and localized electric power systems…

One of my favorite classes, years and years ago as a first year college student, was a lecture course in etymology: the study of the history of words. The professor taught the work as an oral recitation, and essentially progressed through a huge compendium of words (that were selected, printed, and loose-bound at a Kinko’s store), telling us stories surrounding the origins and histories of so many of our terms used in the english vernacular (there’s another one! vernacular—more on that later…). I was hooked, and still get such a kick out of words and the contextual stories that words help to shape. One of my favorite resource sites is the Online Etymology Dictionary by Pennsylvanian, Douglas Harper. Try it out some time, it’s fun–for example:

heliotrope (n.) “plant which turns its flowers and leaves to the sun,” 1620s, from French héliotrope (14c., Old French eliotrope) and directly from Latin heliotropium, from Greek heliotropion “sundial; heliotropic plant,” from helios “sun” (see sol) + tropos “turn” (see trope). In English the word in Latin form was applied c. 1000-1600 to heliotropic plants. Related: Heliotropic.

–credit: D. Harper

Think of the space in which society has time and need to observe plants following the Sun in the first place? Do you have that time and patience to recognize that the light of the Sun is causing a motive response in plants? Big fields of sunflowers can be observed to be following the sun over the course of the day in a wonderful display of heliotropism. Here is an example of heliotropism in the Artic filmed by photographer Dr. Michael Becker, where poppy flowers are tracking the light of the Sun in an entire circle during the summer above the Artic Circle, when the Sun never sets. The beginning is slow, but midway through you can see a section where the sun passes into the frame of view–a spectacular display.

-credit: Michael Becker

Let’s review one more important term, yet with a more ominous origination that ought to make you uncomfortable:

vernacular (adj.) c. 1600, “native to a country,” from Latin vernaculus “domestic, native, indigenous; pertaining to home-born slaves,” from verna “home-born slave, native,” a word of Etruscan origin. Used in English in the sense of Latin vernacula vocabula, in reference to language. As a noun, “native speech or language of a place,” from 1706.

For human speech is after all a democratic product, the creation, not of scholars and grammarians, but of unschooled and unlettered people. Scholars and men of education may cultivate and enrich it, and make it flower into the beauty of a literary language; but its rarest blooms are grafted on a wild stock, and its roots are deep-buried in the common soil. [Logan Pearsall Smith, “Words and Idioms,” 1925]

–credit: D. Harper

A word so loaded from it’s historic use, and so useful to us now as we look to a different kind of future, in a climate changed about our livelihoods. As used by the world of architecture, “vernacular architecture” is a very common phrase, refering to localized building design practice that has evolved as a common knowledge over generations, to serve a practical purpose for society within that particular space and time, something we call: locale. Now, I want us to embrace the scoping of knowledge or skill that emphasizes the role of knowledge that is “domestic, native, indigenous”, or otherwise inter-generational local knowledge. Let’s work that adjective into a new space, the space of a noun, a thing. That is, it may so happen that the solar vernacular of buildings, farming, and food is “not of scholars and grammarians”, and at the same time is more powerful, beautiful, and non-displaceable for local communities.

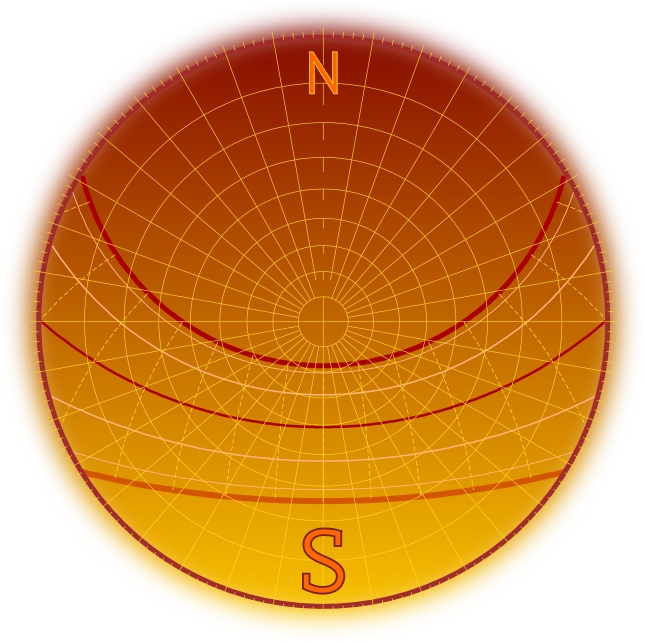

And so we finally come back to the motivating question: Why “Heliotactic”?. For me, it means going back to the word (the etymology), and exploring the space about it, the new contexts emerging, and the potential that the word has for new meaning in our future. Take the greek helios as “sun” + greek táxis (nope, not the car) referring to “arrangement, an arranging, the order or disposition of an army, battle array; order, regularity” (HT to D. Harper once again…). Heliotactic is the adjectival variant of heliotaxis, the noun refering to organism movement toward (or away from) the light of the Sun. You can start to see references to movement and adaptation, and arrangement of actions relative to the light of the Sun. Wonderful, and romantic, and emotive–great. But then again, this is the English language, and (as with vernacular) modern adjectives have the tendency to make their way into the space of nouns (i.e. a nominalized adjective). And so we have heliotactic, a word framed in this new context-dependent solar school of thought called solar ecology to refer to the very pragmatic arrangement of strategies, tactics, common language, and regularity of effort to enable the disposition of an army of solar participants to enact change in society. Heliotactic becomes a new persona to embrace, in this Quixotic press for a new way to think about those big words: light, energy, and solar, and a new way to communicate with each other regarding a potential that is rich, local, and motivating. As L. Pearsall Smith noted:

its rarest blooms are grafted on a wild stock, and its roots are deep-buried in the common soil.

Words have power.

“Have at thee, coward!”

Light will out.

-JRSB